Meet the Entrepreneurs at the Forefront of the Space Race

Call it the New Space Age. There's a reignited fervor for all things extraterrestrial, and entrepreneurs are leading the charge. From zero-gravity tourism to satellite and software development, themed entertainment and beyond, commercial enterprises are capitalizing on opportunities in the burgeoning space industry. As costly and risky as these endeavors may be, the possibility for reward is out of this world.

Almost half a century after Neil Armstrong stepped on the moon, entrepreneurs are titillating the public's imagination with extraterrestrial possibilities once again.

Ground control to Major Branson: Put your helmet on.

Image credit: Virgin Galactic

SpaceX founder Elon Musk has stated that his company could land humans on Mars in the next 10 or 12 years (despite setbacks such as the explosion of an F9R test vehicle in August). Commercial flights on XCOR Aerospace reportedly could start as early as 2015, with tickets going for about $95,000 each. Virgin Galactic, perhaps the best-known carrier of them all, has its sights set on commercial space flights this year.

"This is a very exciting time to participate in the space industry," says Virgin Galactic's Sir Richard Branson. "There is so much room for commercial companies to work alongside government to send people up to space, bring in new investment and prove there is a market for customers who want to go to space."

The efforts of Branson and other entrepreneurs have reignited the fervor of the Space Age. It could be the 1960s all over again, but with one important difference: This time, innovation is intentionally driven not by monolithic governments.

"Lots of people think of space in a kind of 'space race' model, but these days it's much more collaborative," says Mark R. Johnson, a researcher from the University of York who has been studying the internal workings of the U.K. space industry. "It's much more cooperative and more focused on private money, business and infrastructure now."

Ever since NASA adopted a decentralized market approach in 2005, awarding contracts to its low-Earth orbit portfolio to private players like SpaceX and allowing the companies to market their services to the public, a surge of interest has come from the tech-savvy and well-funded, who realize that space is just another venue to expand upon businesses that already exist on Earth. Case in point: In May, FedEx introduced its Space Solutions service for the industry, which aims to walk customers through the intricacies of shipping satellites and other sensitive equipment, with the slogan: "Helping you launch on time."

Space Adventures' suborbital vehicle takes two passengers 10 times higher than the altitude reached by a commercial aircraft.

Image credit: Space Adventures

"Space is a horizontal that cuts across lots of different industries," says Chad Anderson, managing director of Space Angels Network, which connects investors to entrepreneurs to encourage private investment in commercial space and aerospace ventures. "It's just a different place of doing business."

The global space economy has grown by more than 50 percent since 2005, according to Space Foundation in Colorado Springs, Colo. For the past five years, the industry has grown an average of 4.9 percent annually, reaching a record $314.17 billion in 2013. Three-quarters of that growth comes from commercial endeavors.

TOURISTS IN SPACE

The commercial growth has been a long time coming, says John Spencer, founder and president of the Space Tourism Society, a tireless cheerleader for the industry since the 1990s. He points to pioneers such as Branson, Jeff Bezos and Paul Allen. "They all grew up during the Apollo era," he says. "Astronauts were like heroes to them. Once they grew up and became wealthy enough, they migrated essentially to the space world, because that's the ultimate challenge."

Eric Anderson is one such case. After myopia put a halt to his dreams of becoming a pilot, he focused on aerospace engineering and became the first to demonstrate that customers would pay for a truly out-of-this-world experience. Together with Peter Diamandis, who created XPrize to kick-start commercial spaceflight, and Mike McDowell, an adventure-travel operator who routinely sent high-paying customers on underwater voyages in Russian submersibles, Anderson founded Space Adventures in 1998. The Vienna, Va., company has sold rides aboard the Russian Soyuz to the International Space Station to seven well-heeled passengers, including former NASA engineer Dennis Tito (who became widely known as the first space tourist after his 2001 voyage) and Cirque du Soleil founder Guy Lalibert?. Prices reportedly run up to $30 million.

For those who can't pay that, Space Adventures offers a more affordable option. In 2008, it acquired Zero-G, the only FAA-approved provider of weightless flights to the public. Some 12,000 people have taken the zero-gravity flights, with tickets starting at $4,950. Both of Anderson's companies have been profitable for a few years now. "It's turned out pretty good so far," he replies modestly when asked about earnings.

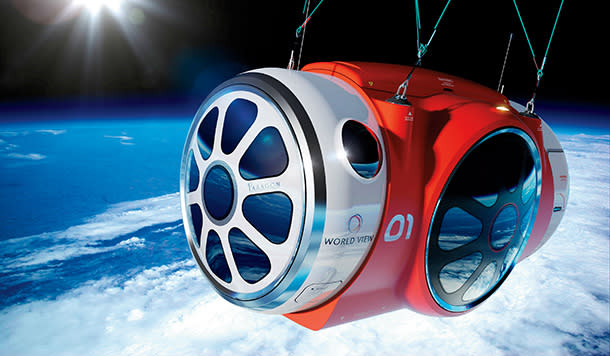

A seat aboard World View's pressurized flight capsule comes with Wi-Fi and a cocktail.

Image credit: World View

The newest entry to the game, Tucson, Ariz.-based World View Enterprises, touts four- to five-hour voyages to the edge of space aboard a pressurized flight capsule hung beneath a parafoil and a high-altitude balloon. Unlike with Space Adventures, there will be no space-flight training, no body-wracking G-forces--only smooth sailing, with Wi-Fi and cocktails, for $75,000.

"We want to give people the opposite experience that you might think of when you think about space travel. It's gentle and slow. It's beautiful," says World View CEO Jane Poynter. "You'll glide up to 100,000 feet, stay up there for hours, looking out this beautiful window with a martini or beverage of choice, and then come gliding back down again."

Though initial flights are still two years away, Poynter says World View has already sold "several flights." The company's customers won't be able to claim that they actually traveled to space, however: World View flights will reach about 20 miles above Earth, far short of the 62-mile mark that officially demarcates space. But the same challenges to human spaceflight persist, such as the need for a pressurized capsule.

World View's gentler travel experience has earned the company backing from Tony Hsieh's VegasTechFund and Philippe Bourguignon, CEO of luxury resort group Exclusive Resorts and former chairman and CEO of Euro Disney. It helps, too, that Poynter is no stranger to space enterprises. Before heading up World View, she co-founded Paragon Space Development, which created life-support and thermal-control systems for extreme environments. Paragon contracted with the likes of NASA, Lockheed Martin and Boeing.

Virgin Galactic is counting on the same adventurous impulse to shore up its business. Owned by Branson's Virgin Group and Abu Dhabi-based Aabar Investments, the commercial spaceliner has convinced about 700 passengers--including Leonardo DiCaprio, Stephen Hawking and Lady Gaga--to pony up $250,000 each for a two-plus-hour journey. The Mojave, Calif.-based company has already amassed about $80 million in deposits. Originally expected to take place in 2007, the spaceliner's maiden voyage has been repeatedly pushed back. Now the company hopes to launch by the end of this year.

"Virgin Galactic aims to offer consumers something truly unique," Branson says. "The ability for private citizens to journey in a spaceship going at three and a half times the speed of sound, go to space, enjoy the views of our home planet in the silence and blackness of space and float in weightlessness."

Image credit: World View/J. Martin Harris Photography

BEYOND JOY RIDES

Though it may seem yet another lark aimed at the super-wealthy, Virgin Galactic has a more practical agenda in mind than simple space jaunts. Branson hopes the company's voyages will set the foundation for speedier suborbital intercontinental travel. The magnate points out: "It is the first of many firsts we will offer with the technology we are developing. Imagine the possibilities for point-to-point travel and satellites."

SpaceShipTwo, the plane developed for Virgin Galactic, is demonstrating the technology that could one day be modified to replace the Concorde. These new jets would travel outside the Earth's atmosphere, enter orbit and use gravitational forces to whip around the world at incredible speeds, potentially reducing the 21-hour flight from London to Sydney to a mere two hours.

Utility could be the turning point for the space industry's long-term profitability, if history is any indication. Bob van der Linden, chair of the Aeronautics Department at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum, says leisure-tourism dollars may not be sufficient to sustain a large industry. "If you visit the Grand Canyon, you may get on an airplane to see the view," he says. "That's enough to keep one small company going, but not an international industry. It's just a joy ride. But if businesses can get you from Washington to Japan in 45 minutes affordably, then you may have something."

This pragmatic line of thinking is the reason many businesses have an underlying utilitarian revenue source beneath their lavish offerings. In addition to its passenger flights, World View, for example, wants to cater to the needs of businesses. Using the same high-altitude balloon setup but replacing the pressurized capsule at its tail, World View could tether other instruments to be used for communication, surveillance or first-response systems. World View has dubbed this niche "stratollites."

"You can fly higher with more mass than you can with a commercial drone," Poynter explains, "or you can fly lower, slower, less expensively than most satellites." World View projects that tourism will provide much of the company's revenue in the short term, but more business will eventually flow from a growing satellite market.

Virgin Galactic is betting the same. The company is working with Northrop Grumman, which was awarded a $4 million contract from Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, on an experimental space plane that could help launch satellites at a fraction of the current cost. (Two other teams received similar contracts: Boeing with Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin, and Masten Space Systems with XCOR Aerospace.)

"There are currently 3 billion people without access to the internet," Branson says. "Imagine what would happen to their lives if they were able to better monitor treatment of health and disease, gain employment, get access to education and alternative banking solutions, all through the internet. That's what we hope to do through low-cost satellite launches."

STARTUPS GET IN THE GAME

Though deep-pocketed business mavens dominate the playing field, they don't control it completely, as four Stanford grads have proved. Dan Berkenstock, John Fenwick, Ching-Yu Hu and Julian Mann founded Skybox Imaging in 2009 as part of a graduate entrepreneurship course. The company has developed a proprietary data platform to process, store and deliver data extracted from images taken by its satellites. Once the full constellation of 24 satellites is up, Skybox will be able to take photos of any spot on Earth up to five times a day. Such data could be used to forecast crop yields, gain information about the effects of natural disasters and even aid first responders in rescue coordination.

The plan scored $3 million in Series A funding from Khosla Ventures and eventually raised $91 million. Skybox, which has grown to 125 employees, launched its first satellite last year aboard a Russian rocket, its second went up in July, and plans are to launch seven more in 2015. Customers can order individual images or subscribe to a stream of images, data and analytics.

The information-based business model caught the eye of Google, which in June entered into an agreement to purchase Skybox for $500 million. The information giant currently buys its images from other companies; the use of Skybox's satellites will help keep Google Maps accurate with more frequent, up-to-date imagery.

"Hardware-based investments need longer lead times and more capital to make a return, but that's not always the case," says Space Angels Network's Anderson. "Skybox didn't even have its business up and going; they had a prototype in the air. But they were able to sell their business with Google. Things are changing, and quickly, in the sector."

On top of the world, looking down: a Skybox Imaging satellite photo of Turkey.

Image credit: Skybox Imaging

The success of Skybox proves that there is a place for scrappy startups without millions of dollars of personal wealth to tap. "There's room now," says Micah Walter-Range, director of research and analysis at the Space Foundation. "It's a good time to get into the space business simply because the barriers are low enough that you can do it and be successful."

Walter-Range says most opportunities for startups are in building satellites or their components. "If you can come up with a really good sensor that does whatever it does better than everyone else, there will be a demand for that," he says.

More and more, universities and startups are launching nanosats: small satellites weighing a few pounds, at costs of $150,000 to $1 million, vs. the $200 million to $1 billion price tag of full-scale models.

But space isn't just the realm of tech sophisticates. Apart from championing the prospects of space for the Space Tourism Society, Spencer has made a living off the intersection of space and design for almost four decades. He has designed space facilities and ship interiors for NASA and other enterprises, as well as space-themed attractions and resorts, since 1978.

Spencer helped develop the interiors for the first version of the International Space Station and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Aquarius Underwater Laboratory near Key Largo, Fla. While awaiting new contracts from NASA and the like, his income stems from themed entertainment. He designed the concept and master plan for the Space World theme park in Japan and is working on a new venture, Mars World, a $1.8 billion theme park in Las Vegas, with Lewis Stanton, managing partner of Stanton Associates.

Mars World Enterprises, which owns the brand Mars World, has raised $200,000 of the $250,000 it needs to start the project. With the help of Santa Monica, Calif.-based investment bankers DelMorgan & Co., Mars World is looking to raise another $9 million to cover two years of development for the theme park. Based on the designs, engineering and feasibility studies developed during that period, Spencer expects to raise the $1.8 billion needed to open by 2019, the 50th anniversary of the first lunar landing.

The goal, Spencer says, is to eventually sell the first theme park to a real-estate company but maintain rights to the brand, enabling Mars World Enterprises to build similar parks in other locations. "We're executive producers," Spencer says. "We would sell the park to permanent owners."

The space architect is confident he has a winning idea, pointing to the popularity of Star Trek, Avatar and even the Harry Potter series to make his case. "Each of these invented worlds was created by just one person," Spencer says. "The difference for us is that one day this is all going to be real. Every day, you get closer to the day humans could walk onto Mars. There will eventually be immigration settlements, habitats, cities on Mars. All the developments in the real world on that front will only build our brand value."

EXPANDING TO NEW MARKETS

Space can sometimes be a savvy extension for an existing enterprise. Jay Johnson, president of Garden Grove, Calif.-based Coastline Travel Advisors, signed on to be one of Virgin Galactic's "accredited space agents" because it made sense for his business. "We specialize in high-end luxury travel," Johnson says. "Virgin Galactic is the pinnacle of adventure traveling. It can't get more adventurous than that."

Since signing up for the program in 2007, Johnson has sold eight trips--more than anyone else in North America. His decision also had a welcome side effect: Coastline has picked up a few more regular clients because of his association with the space carrier. "People who have found us because of Virgin Galactic have become regular clients, because they can see that we can do other things. Someone that wants to go on a trip to space is just as inclined to hike the Inca trail in Peru or shark dive in Cape Town," Johnson says. He estimates that his association with Virgin Galactic has earned his business $2 million over the past seven years.

Image credit: Virgin Galactic

Space may connote adventure, says Eric Anderson, but it's also a matter of survival. His most audacious venture is Planetary Resources (another company co-founded by Diamandis), which aims to use unmanned spacecraft to mine asteroids for precious minerals.

In one scenario, asteroid-sourced hydrogen and oxygen could be used to create rocket fuel that would power space shuttles, tugs assigned to keep geostationary satellites in their orbits or spaceships on deep-space voyages. Anderson estimates that the amount of fuel available in one medium-size near-Earth asteroid would have been enough to launch all 135 Space Shuttle missions since the beginning of the program in 1981. Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson publicly endorsed the scheme as "no bullshit" in a 2012 appearance on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart.

Founded in 2010, Planetary Resources boasts well-known investors such as Branson, Larry Page and Eric Schmidt of Google and two-time space tourist and philanthropist Charles Simonyi. Anderson says the company will begin extracting materials from asteroids within six years. He adds: "We'll be setting up fueling stations throughout the solar system, creating networks where companies can go, buy materials and build space stations. Ultimately, we'll use all of that infrastructure to build and sustain life on other planets."

Space may be the final frontier, but businesses still have to face very real obstacles to earn their rewards. The most significant problems, according to Johnson at the University of York, continue to be "cost, risk and length of time." According to research he has conducted with U.K.-based space businesses, the industry has a failure rate of about one in 50, on top of its ultra-long technology development cycle.

"There will be one failure that might cost $150 million or more for every 50 things that has to be done," he says. "It can be an explosion on the launch pad, failure to orbit or a breakdown during orbit. There are lots of failure stages here."

Despite such risks, entrepreneurs continue to forge the path, because to them space represents a relatively untapped, exponentially profitable market--and one that's crucial to mankind's prosperity going forward.

"All the things we have on Earth, materially, that we negotiate over, tax, fight wars over--those things are available in infinite quantities in space," Anderson says. "If we as a society choose not to explore space and turn inward, within hundreds of years, we will run out of resources. Space exploration will ensure our survival as a human race for our children and our grandchildren for hundreds of thousands of years, if not more."

More From Entrepreneur

Yahoo News

Yahoo News